Blip-Zip Executive Summary

Are you tired of Band-Aid solutions for homelessness? This article exposes the limitations of shelters and proposes a powerful alternative: Systems Thinking! Learn how upstream leadership can tackle root causes like mental health, affordable housing, and joblessness. Discover the shocking costs of chronic homelessness and the potential for lasting solutions. Check out the questions, learning activities, and resources at the end to become a homelessness prevention champion!

Blip-Zip Takeaways

- Shelters are a temporary fix, not a solution. Upstream leadership focuses on prevention.

- Systems thinking helps identify root causes and leverage points for lasting change.

- Strategic investment in affordable housing, mental health services, and jobs ends the homelessness cycle.

Key Words and Themes (#Hashtags)

#HomelessnessPrevention #SystemsThinking #UpstreamLeadership #AffordableHousing #MentalHealth #Jobs #CommunityCollaboration #PublicHealth #SocialServices

Table of Contents

Introduction: Systems Thinking Tools To End Homelessness

Do you lead healthcare, social services, or public health? Do you want to change your community? Thus, understanding the causes of homelessness is crucial. Despite their good intentions, shelters often bandage deeper wounds. They ignore mental health, addiction, affordable housing, and job opportunities. The result? a cycle of homelessness, frustration, and high healthcare costs. Want to break the cycle and make a difference?

Jump in!

The US and Canada have hundreds of thousands of homeless people every night. Homelessness is a global public health and environmental issue, many times worse. On any night in January 2020, 580,466 Americans (18 out of 10,000) were homeless, a 2.2% increase from 2019. While 61% of people experiencing homelessness were in sheltered locations, over 226,000 were on the streets, in abandoned buildings, or other unsuitable locations. The facts are shocking:

- Homelessness has risen for four years.

- Unsheltered homelessness is rising mostly in California.

- One night in 2020, 171,575 families with children were homeless.

- There were 3598 homeless children under 18 without adults.

- Veterans comprised 8% of homeless adults (46,000+).

- People of color are overrepresented among homeless people.

There’s hope! Systems thinking helps us see the big picture and find change levers. This article provides real-world examples and a roadmap for upstream leadership to help your community end homelessness.

Widespread Problem – Any Community or County

For city and county officials, community leaders, and health providers, placing homeless individuals in shelters is the most inexpensive and humane way to meet the basic needs of individuals experiencing homelessness. Some may even believe shelters are an ideal solution. Are they? NO!

Homelessness is a complex issue that requires a systemic approach. While placing homeless individuals in shelters may seem like a quick and inexpensive solution, it only masks the underlying causes of homelessness. Shelters may offer temporary relief by providing basic needs like food and a bed. However, they become overcrowded, leading to limited resources and decreased quality of care.

Additionally, shelters fail to address the root causes of homelessness, such as mental health issues, addiction, and joblessness. As a result, individuals may cycle in and out of shelters without receiving long-term support. Just ask the community leaders in Martinsburg, West Virginia. The case study is accurate and revealing.

Many believe the problem is too complex to solve or someone else’s problem. A systemic approach that incorporates affordable housing, healthcare, job training, and mental health services is necessary to address homelessness effectively.

This approach should consider the social determinants of health (SDOH), the circumstances where individuals are born, live, work, and age. It should also consider the systems they use to deal with crises, security, and illnesses. We can develop lasting solutions to homelessness by focusing on these underlying factors.

It’s Not Just The Shelter!

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, the challenge worsened because of the pandemic, rising from 582,000 people in 2022 to more than 653,000 in 2023. Focusing solely on shelters fails to address the root causes of homelessness. For lasting solutions, a systemic approach that incorporates affordable housing, job training, health and behavioral services is needed.

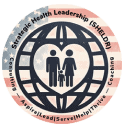

Healthy People 2030, as highlighted in the figure below, highlights the importance of the social determinants of health or circumstances where individuals are born, live, work, and age. It also highlights the systems they use to deal with crises, security, and illnesses.

Health starts in the individual’s homes, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, and communities. Figure 1

Figure 1: Social Determinants Of Health about Homelessness

Homelessness or unstable housing represents a significant social determinant of health. Accommodation and employment are two social determinants of health that work together, significantly impacting health outcomes. The conditions in which individuals live explain why some Americans are healthier than others or not as healthy as they could be.

The social determinants of health within Healthy People 2030 are designed to create social and physical environments that promote good health.1 Unemployed individuals are more likely to self-report worse health status, experience more depression symptoms, and are at a higher risk for mortality.2 Unfortunately, homelessness contributes to poor health and prosperity for individuals and communities.

Downstream Costly 2nd and 3rd-Order Effects on Healthcare

Homeless patients often experience poor health outcomes due to their living conditions, psychosocial stress, and food insecurity. They also have limited resources for self-care and tend to use healthcare services more than other patients. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), homeless single men visit emergency departments nine times more often than others, while homeless single women visit 12 times more, and homeless adults in families visit 3.4 times more.

Hospitalization rates are also much higher in homeless individuals, with rates of 8.5 times higher among homeless single males, 4.6 times higher among homeless single women, and 2.1 times higher among homeless adults in families. Homeless people often face chronic health conditions, mental illness, substance use, and engage in risky health behaviors. They are also more likely to be poor and unable to afford basic needs like food and clothing.3

Homelessness is expensive for both communities and taxpayers due to costs associated with hospitalization, treatment, incarceration, police intervention, and emergency shelter. Homeless individuals also spend an average of four extra days in the hospital compared to non-homeless patients, costing an additional $2,414 per hospitalization.1

Similarly, a study in Hawaii found that treating homeless individuals costs $3.5 million in excess or about $2,000 per person. A homeless patient with diabetes may have difficulty managing their condition due to a lack of a storage place for their insulin or due to poor access to nutritious food. 2.

According to a New England Journal of Medicine report, people experiencing homelessness spent an average of four days longer per hospital visit than a comparable non-homeless patient. This extra cost, about $2,414 per hospitalization, is attributable to homelessness.4

Similarly, a study of hospital admissions of homeless individuals in Hawaii indicated that 1,751 adults were responsible for 564 hospitalizations or $4 million in costs. Their rate of psychiatric hospitalization was 100 times higher than their non-homeless cohort. The study’s researchers estimated the excess cost of treating homeless individuals was $3.5 million or about $2,000 per person.5

Homelessness crosses many civilian and governmental sectors at all levels. For example, a study examined health service utilization and costs for homeless and domiciled veterans hospitalized in psychiatric and substance abuse units at all Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Of the 9,108 veterans surveyed, 20% had been homeless at the time of admission; 15% of the veterans had doubled in shelters, for a total homelessness rate of 35%. After adjusting for other factors, the average annual cost of care for homeless veterans was $27,206. Twenty-six percent of annual inpatient VA mental health expenditures are spent on the care of homeless veterans.

Homelessness adds to the cost of health care services for veterans with mental illness in the VA. These results are most likely similar to other “safety net” systems serving people experiencing poverty.6

Homelessness affects many sectors, including healthcare, and addressing this problem requires a complex, systems-based approach. Homelessness both causes and results from acute healthcare issues like addiction, psychological disorders, and HIV/AIDS. This inability to treat medical problems makes them more dangerous and costly. For example, the average cost to cure an alcohol-related illness is approximately $10,660.7

Another study found that the average cost to California hospitals of treating substance abuse is about $8,360 for those in treatment and $14,740 for those who are not.7

The challenge of ending homelessness is complex. Systems thinking can help develop a shared understanding of why chronic, complex problems exist and where leverage points are to solve problems sustainably. Homelessness inhibits care, and housing instability detracts from regular medical attention, access to treatment, and recuperation.

Hypothetical Case: Stock and Flow and Causal Loop Diagrams

According to the January 2022 PIT Count, 582,462 people were experiencing homelessness across America. This amounts to roughly 18 out of every 10,000 people. The vast majority (72 percent) were individual adults, but a notable share (28 percent) were people living in families with children.

A community’s “Homeless Coalition” successfully addressed chronic homelessness in County-X by using systems thinking tools and discussing perspectives from multi-sector stakeholders, leading to lasting social impact over ten years.3 This composite case study illustrates how a community’s “Homeless Coalition” addressed chronic homelessness surrounding County-X.

Despite County-X’s efforts, City-X, with a population of 100,000, has been unable to address the homelessness problem. The issue is not about lack of knowledge or best practices but rather about community actors and stakeholders developing a shared vision based on system dynamics and establishing common goals to transform the current community-based system. 8 Participants identified the problem’s size and interconnectedness through interviews, focus groups, and systems thinking tools. The team clarified change incentives and helped each team understand their responsibility towards achieving the desired state.

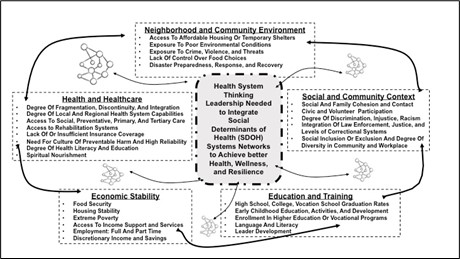

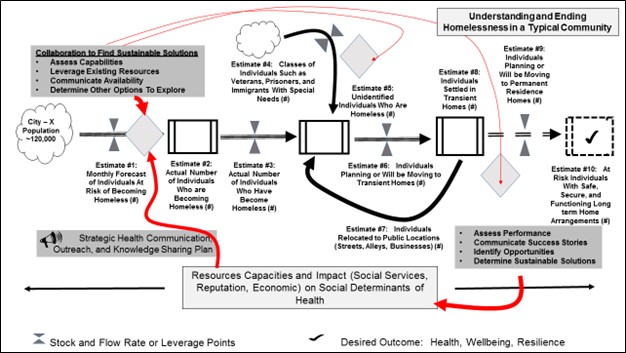

The analysis reveals a four-step scenario with stock flow and causality loop diagrams illustrating the stages of homelessness. The individuals are at risk of losing their homes, living on the streets, finding temporary shelter, and relocating from temporary shelter to permanent housing. Figure 2 illustrates the stages of homelessness with stock and flow rates or leverage points for policy intervention.

Figure 2: Stages Of Homelessness With Stock And Flow Rates Or Leverage Points

- Risks Result in Homelessness: Individual risk factors, limited permanent jobs, financial problems, and social risks contribute to homelessness. As the availability of affordable housing decreased, landlords faced economic challenges, which reduced the availability of affordable housing, leading to more homelessness. Community organizations, state and social services agencies, government subsidies, family, friends, churches, and schools offered support and information about available resources. Veterans Affairs also offered transitional support to veterans. However, these efforts were not enough to create momentum, leading many individuals to fall into the homelessness cycle or resort to hiding-away living arrangements. County-X, home to a Veterans Health Administration psychiatric hospital, saw many veterans seeking treatment in City-X, leaving many homeless or living on the streets or in shelters.8

- Why People Get Off the Streets Only Temporarily: Homeless individuals often resort to temporary solutions, such as 30-day shelters, but usually end up in unsafe housing or emergency rooms. Limited case management resources result in limited support for those experiencing homelessness. Self-determination is crucial for overcoming adversity, but more is needed with infrastructure and services to secure permanent, safe, affordable housing and living wage jobs.8

- What Prevented Individuals from Permanent Housing Arrangements: Leaders have acknowledged the necessity for sustainable solutions, including the provision of essential human services like detox, substance abuse treatment, and mental health services, as well as the provision of safe, affordable housing, living wage jobs, childcare, and transportation services, to ensure a better quality of life. Most important, the community’s organic solutions were limited by several factors, including:

- Time delays in implementing a solution and waiting for results (i.e., expectation of quick fixes versus long-term sustainable solutions)

- Barriers produced by homelessness (e.g., legal identity, poor credit history, evictions, criminal record, negative stereotyping).

- Ability to create permanent, living wage jobs and support

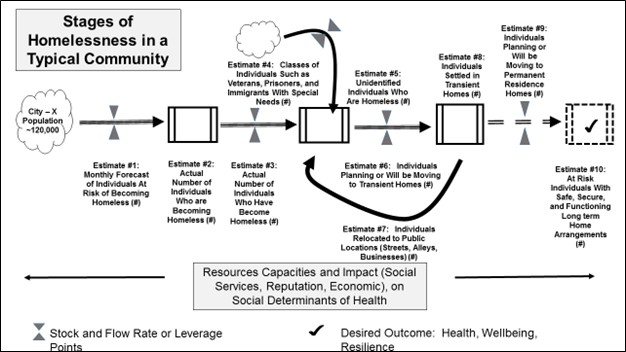

Figure 3 illustrates the system dynamics of temporary shelters, highlighting the barriers and obstacles that hinder individuals’ access to resources and prevent them from moving to permanent housing. These barriers limit opportunities for individuals to improve their life skills and create reluctance for landlords and employers to provide new starts. The lack of visibility of the problem reduces pressure on the community to solve it, and the overnight success of shelters suppresses funding for innovation and collaboration, including the use of existing resources for other initiatives..8

Figure 3: Balancing And Reinforcing Loops Illustrate Homelessness.

Unfortunately, the overnight success led to:

- Fragmentation and lack of awareness of services

- Competition for existing funds and resources (or lack of utilization)

- Lack of broader knowledge of best practices

- Reluctance to overcome government restrictions

- Shelter as “the solution” mentality

These dynamics or balancing loops represent a familiar dynamic of shifting the burden (to the quick fix) or, in psychological terms, “addiction” found in many complex social systems where a quick fix undermines sustainable solutions.17

Applying Leverage Points

This case study highlights two significant interventions that can help end homelessness. The first intervention involves increasing and accelerating the number of individuals moving from temporary shelters into permanent housing, while the second intervention reduces the risk of becoming homeless in the first place.8 Figure 4 illustrates how applying collaboration and communication at key stock and flow points results in better decisions.

Figure 4: Applying Collaboration and Communication to Make Decisions

The coalition aimed to increase the visibility of a problem by providing accurate information about its extent and community motivation to solve it permanently. Collaboration, alignment, and investment among providers and the community were crucial to reducing fragmentation, limiting a shelter mentality, increasing knowledge of best practices, and overcoming government restrictions.

The local health system established stable primary care services modeled after a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) for homeless patients, including walk-in visits, team care, mobile and on-foot units, and access to a local shelter and medical respite program for post-hospital transitions.2

The most cost-effective solution to homelessness is to increase access to permanent, safe, affordable, healthy, and supportive housing. This can be achieved through substance abuse and mental health treatment for specific populations and through economic development partnerships. Additionally, ensuring access to living wage jobs is crucial. Strategies to help at-risk individuals retain their homes include supporting landlords in renting to at-risk individuals and creating sufficient living wage jobs to enable them to pay rent.8

Upstream Leadership’s Solutions to Chronic Homelessness

Chronic homelessness is a complex issue with devastating consequences for individuals and communities. While shelters and emergency services play a vital role, they are often reactive solutions. Upstream approaches that address the root causes of homelessness are crucial for long-term success. The table explores how key community organizations are impacted by chronic homelessness and the upstream actions they can take to prevent it.

Table 1: Community Organizations and Upstream Solutions for Chronic Homelessness

| Organization and Interest in Homelessness | Upstream Leadership Actions |

| Affordable Housing Developers: Reduced demand for emergency shelters, increased occupancy rates | Advocate for inclusionary zoning policies requiring affordable units in new developments. Develop mixed-income housing projects that integrate formerly homeless individuals—and partner with homeless shelters to provide transitional housing options. |

| Mental Health and Addiction Treatment Centers: Improved access to mental healthcare, reduced substance abuse leading to homelessness | Increase outreach programs to connect homeless individuals with mental health and addiction services. Advocate for funding and expansion of mental health and addiction treatment programs. Develop specialized treatment programs tailored to the needs of the homeless population. |

| Domestic Violence Shelters: Reduced need for shelters due to domestic violence, increased safety for victims | Provide safe havens and support services for victims of domestic violence to prevent homelessness. Advocate for more robust domestic violence prevention programs. Collaborate with affordable housing providers to create safe, long-term housing options for survivors. |

| Schools: Improved attendance and academic outcomes for children experiencing homelessness | Implement early identification programs to identify students at risk of homelessness. Provide on-site resources and support services for homeless students and families. Advocate for funding for homeless student support programs and educational stability grants. |

| Hospitals and Healthcare Providers: Reduced healthcare costs associated with chronic homelessness, improved health outcomes for homeless individuals | Implement outreach programs to connect homeless individuals with preventative healthcare services. Offer on-site or mobile clinics for homeless individuals to address chronic health issues. Advocate for policies that expand healthcare access for low-income populations. |

| Law Enforcement: Reduced crime rates associated with homelessness, improved public safety | Implement crisis intervention training (CIT) programs for police officers to de-escalate situations involving homeless individuals—partner with social service providers to connect homeless individuals with appropriate resources. Advocate for funding for social programs that address the root causes of homelessness and reduce crime. |

| Faith-Based Organizations: Strengthened communities, fulfilling religious missions of helping the less fortunate | Provide emergency shelter, food pantries, and clothing distribution programs to meet basic needs. Advocate for affordable housing initiatives and policies that support homeless individuals. Offer job training and employment programs to help homeless individuals achieve self-sufficiency. |

| Employers: Access to a larger pool of qualified workers, improved company image | Partner with job training programs that serve homeless individuals. Offer fair wages and benefits that allow employees to afford housing. Implement flexible work schedules to accommodate individuals with childcare or transportation challenges. |

| Public Transportation Agencies: Increased ridership, improved accessibility for all community members | Offer reduced fare programs for low-income individuals and those experiencing homelessness. Expand public transportation routes to connect homeless shelters and services with job opportunities. Ensure public transportation infrastructure is accessible for individuals with disabilities, often a factor in homelessness. |

| Landlords and Property Managers: Reduced vacancy rates, increased rental income | Participate in rental assistance programs that provide subsidies for low-income tenants—partner with homeless shelters and service providers to screen and place formerly homeless individuals in stable housing. Advocate for policies incentivizing landlords to rent to individuals with housing vouchers or rental assistance. |

Community organizations can play a crucial role in preventing chronic homelessness by taking a proactive approach. Collaboration and upstream leadership focused on affordable housing, mental health services, domestic violence prevention, education, healthcare, public safety, and employment opportunities are essential for creating a more supportive and inclusive community.

As homelessness and unemployment persist in the country and worldwide, community health leaders should look to these systems thinking examples to provide comprehensive care, improve health outcomes, and reduce health costs. In the case of homelessness, a health, social, and economic issue, making these advances involves working together, establishing shared goals, and maximizing opportunities for collaboration at all levels.

When integrated with community approaches to foster collaboration, systems thinking enables actors and stakeholders to move from misperceptions to understanding best practices to a shared commitment to creating community-wide sustainable solutions.8

Ending Homelessness: A Call to Strategic Upstream Leadership

This in-depth analysis of homelessness revealed a powerful solution: systems thinking. It calls for strategic upstream leadership beyond shelters. This proactive approach addresses mental health, affordable housing, and unemployment as causes of homelessness. This summary highlights key takeaways and emphasizes strategic upstream leadership to end homelessness. Shelters alleviate temporary homelessness but do not address root causes. Systems thinking promotes collaboration and identifies intervention points for systemic change.

Strategic upstream leadership prioritizes prevention by creating affordable housing, mental health services, and job opportunities. Chronic homelessness is costly for health and human services and co-payers. Communities can make lasting progress by focusing on prevention. Imagine a future where homelessness is rare. This vision is achievable with strategic upstream leadership and systems thinking.

What upstream solutions can you promote in your community?

Deep Dive Discussion Questions

- Rethinking Shelters: A Band-Aid or Stepping Stone: Homelessness shelters provide vital temporary relief, but are they enough? Discuss the limitations of shelters in addressing homelessness. Can shelters play a role in a comprehensive solution? If so, how?

- Upstream vs. Downstream: A Shift in Focus: What are some examples of upstream interventions for homelessness prevention? How can you identify upstream solutions within your expertise (healthcare, social services, etc.)?

- Collaboration is Key: Building a More Supportive Community: Imagine you are leading a task force to address homelessness in your community. Which stakeholders would you involve? How would you foster collaboration to create a more supportive environment?

- The Power of Systems Thinking: Seeing the Bigger Picture: Systems thinking encourages us to examine the interconnected factors contributing to homelessness. How can systems thinking be applied to develop more effective solutions for homelessness? Consider a specific cause of homelessness (e.g., mental health issues) and brainstorm how a systems-oriented approach could address it.

- Leading the Charge: Your Role in Ending Homelessness: What initial steps can you take to champion upstream solutions for homelessness within your sphere of influence? How can you leverage your expertise to advocate for change?

Professional Development and Learning Activities

- Case Study Simulation: A Community in Crisis: Imagine you are a public health official in a community experiencing a rise in homelessness. Using systems thinking, develop a plan to address this issue. Identify the root causes of homelessness in your community. Research and evaluate existing upstream interventions. Develop a collaborative action plan involving relevant stakeholders. Create measurable goals and track your progress.

- Building Your Upstream Intervention Toolkit: Research and compile a list of upstream interventions for homelessness prevention within your area of expertise (healthcare, social services, etc.). Identify relevant resources (articles, websites, organizations) for each intervention. Evaluate the feasibility and potential impact of each intervention within your community. Develop a communication strategy to raise awareness about upstream solutions.

- Networking for Impact: Building Strategic Partnerships: Identify key stakeholders who can play a role in addressing homelessness in your community. Develop a plan to connect with these stakeholders and explore potential collaboration opportunities. Research the missions and areas of expertise of relevant organizations. Identify possible points of collaboration and areas of mutual interest. Prepare an elevator pitch to communicate your vision and the importance of cooperation.

Engaging in these activities will deepen your understanding of upstream solutions and develop the skills necessary to become a leader in ending homelessness within your community.

References and Resources

- Addressing Social Determinants of Health Among Individuals Experiencing Homelessness, https://www.samhsa.gov/blog/addressing-social-determinants-health-among-individuals-experiencing-homelessness

- The Cost of Living Index as a Primary Driver of Homelessness in the United States: A Cross-State Analysis, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10574586/

- Reducing Homelessness with Upstream Thinking: How Rockford, Illinois, took on homelessness and won, https://icma.org/articles/pm-magazine/reducing-homelessness-upstream-thinking

- “A Systems Thinking Approach to Addressing Homelessness” (2022): https://www.appliedsystemsthinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TopicalHomelessness.pdf by Austin Griffiths in the Journal of Public Health Management, Practices, and Policy.

- “Upstream Interventions for Homelessness Prevention: A Review of the Literature” (2020): http://www.evidenceonhomelessness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Homelessness_Prevention_Literature_Synthesis.pdf by Stephanie Reich et al. in the Journal of Community Psychology. This article reviews various upstream interventions and their effectiveness in preventing homelessness.

- “Ending Homelessness in America: A Report to the Congress” (2023): https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/12/19/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-plan-to-prevent-and-end-homelessness/ by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This report outlines the federal government’s plan to address homelessness in the United States.

- “The State of Homelessness in Canada 2022” (2022): https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/reports-rapports/pit-counts-dp-2020-2022-highlights-eng.html by the Canadian Homeless Count. This report provides a national snapshot of homelessness in Canada, including demographics and trends.

- Tackling Homelessness: European Approaches to Housing a…. https://www.entrepreneursherald.com/blog/tackling-homelessness-european-approaches-to-housing-and-social-support

- The Social Determinants of Health: Homelessness and Unemployment – America’s Essential Hospitals. https://essentialhospitals.org/quality/the-social-determinants-of-health-homelessness-and-unemployment/

- Fact Sheet: Cost of Homelessness. https://www.npscoalition.org/post/fact-sheet-cost-of-homelessness

Citations

1. CDC. Social Determinants of Health. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy People 2020 Web site. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Published 2016. Accessed.

2. Schrag J. The Social Determinants of Health: Homelessness and Unemployment. 401 Ninth St. NW, Suite 900, Washington, DC 20004: America’s Essential Hospitals;2014.

3. Hwang SW HM. Health Care Utilization in Homeless People: Translating Research into Policy and Practice. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ);2010.

4. Salit S.A. KEM, Hartz A.J., Vu J.M., Mosso A.L. . Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;338:1734-1740.

5. Martell J.V. SRS, Harada J.K., Kobayashi J., Sasaki V.K., Wong C. Hospitalization in an urban homeless population: the Honolulu Urban Homeless Project. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1992;116:299-303.

6. Rosenheck R SC. Homelessness: health service use and related costs. Journal of Med Care. 1998;36(8):1121-1122.

7. Associates A. Costs Associated With First-Time Homelessness For Families and Individuals. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development;2010.

8. Stroh DP, Goodman, Michael. A Systemic Approach to Ending Homelessness. Applied Systems Thinking Journal. 2007;4.